History is often presented as a clean line of events, neatly recorded and responsibly preserved. In reality, it is closer to a manuscript with missing pages, scratched-out names, and entire chapters torn away. What we call history is not only what happened, but what survived power.

Throughout time, rulers, institutions, and empires have understood one truth very well. Control the story, and you control memory. Erasing an event can be more effective than defeating an army. Silence can outlast violence.

One of the earliest examples of deliberate erasure comes from ancient Egypt. Pharaohs routinely removed the names and images of their predecessors from monuments and records, a practice known today as damnatio memoriae. To be erased from history was considered worse than death. When Hatshepsut ruled successfully as pharaoh, later leaders systematically removed her from official history, attempting to rewrite the past as if a woman had never ruled Egypt. Her existence survived only because stone does not forget as easily as paper.

In imperial Rome, censorship took a more bureaucratic form. Historians who criticized emperors risked exile or execution. Records unfavorable to those in power were destroyed or altered. Entire political scandals vanished from official chronicles, leaving modern historians to piece together truth from fragments, letters, and hostile accounts written decades later.

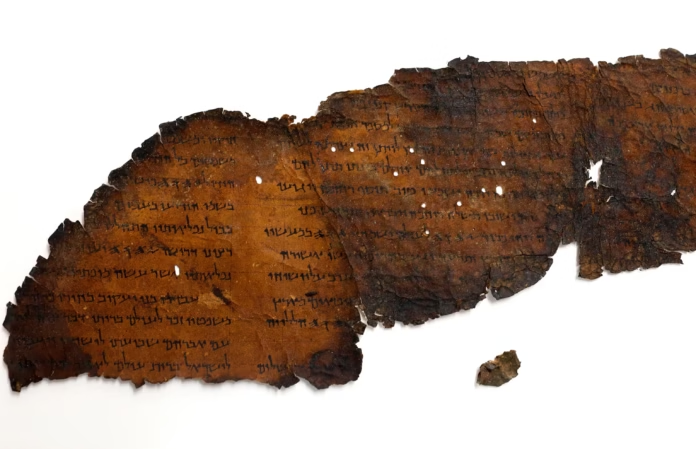

Religion has also played a central role in shaping forbidden history. Early Christian texts that did not align with emerging doctrine were labeled heretical and excluded from scripture. Writings that offered alternative views of divinity, gender, or authority were hidden or destroyed. The survival of some texts, such as those later discovered at Nag Hammadi, revealed how much theological diversity once existed before orthodoxy narrowed the narrative.

Empires fell, but censorship evolved. During the age of colonial expansion, entire civilizations were rewritten by conquerors. Indigenous histories were dismissed as myth. Oral traditions were ignored. Languages were suppressed. When records existed, they were filtered through colonial perspectives that justified domination. Generations grew up learning a version of history that painted conquest as progress and resistance as savagery.

In the 20th century, totalitarian regimes perfected historical erasure. Photographs were altered. Former allies disappeared from records overnight. Schoolbooks changed with each political shift. In the Soviet Union, figures who fell out of favor were not merely punished, they were removed from the past itself. Memory became a tool of obedience.

Even democratic societies are not immune. Wars have been reframed, atrocities minimized, and uncomfortable truths delayed for decades under the label of national security. Archives remain sealed. Whistleblowers are discredited. The public is told some truths are too dangerous to know.

What makes forbidden history so compelling is not only rebellion, but recognition. People sense when a story feels incomplete. Gaps provoke curiosity. Silence raises questions. When something is hidden, the instinct is to look closer.

Recovering erased history is rarely simple. It requires archaeology, linguistics, cross-cultural research, and the courage to challenge accepted narratives. But every rediscovered fragment restores complexity to the human story.

Forbidden chapters remind us that history is not fixed. It is contested terrain. What we know today is shaped by who held power yesterday.

And perhaps the most unsettling realization is this. There are chapters still missing. Stories not yet uncovered. Truths waiting quietly in archives, ruins, and memories, for someone brave enough to turn the page.